Prototyping a Chess Puzzle Game

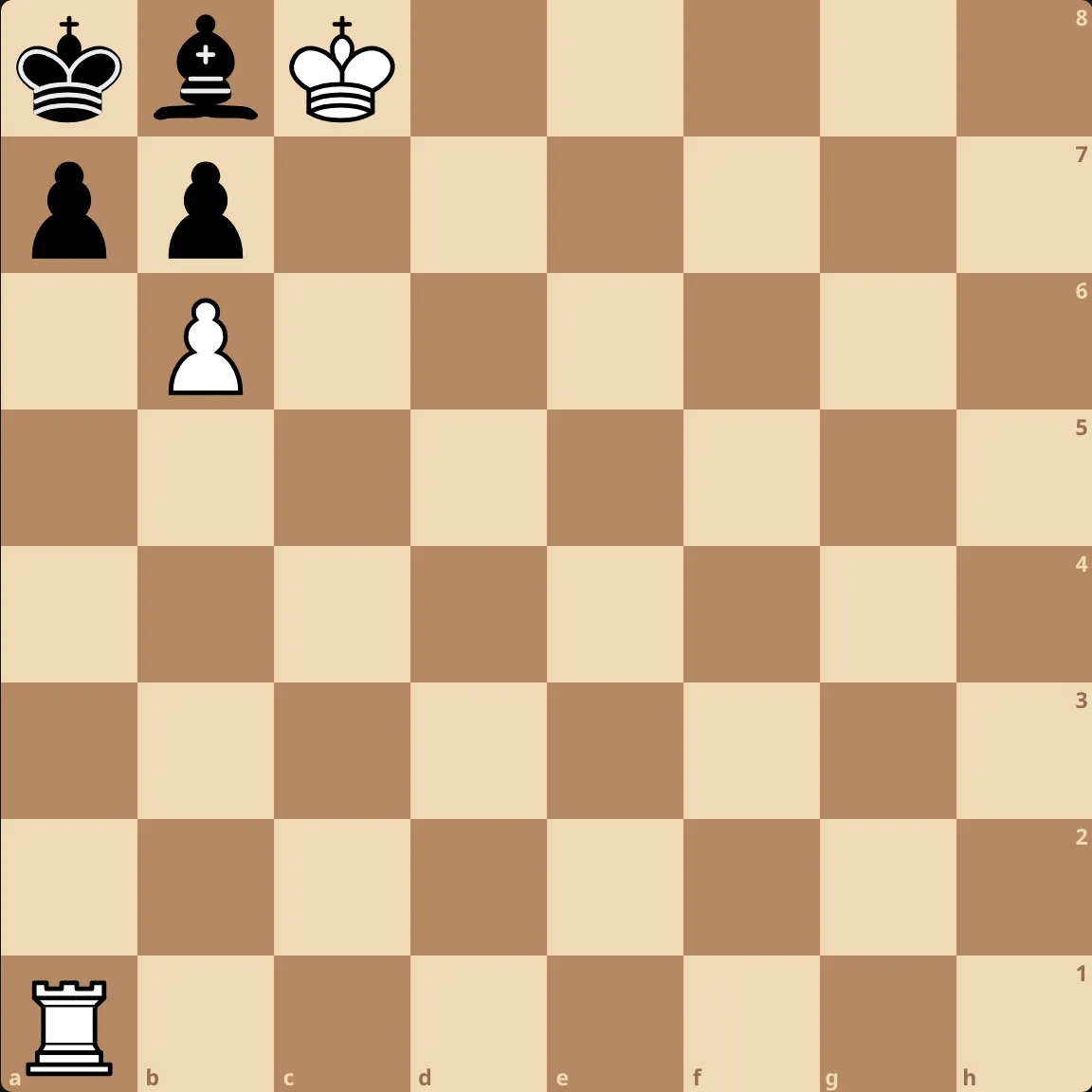

in chess, javascriptMonster Chess is my attempt at a chess puzzle game that doesn’t require any knowledge of chess except the movement of the pieces.

Rules of Monster Chess:

- You can only move white pieces.

- Capturing a piece turns your current piece into the kind that you captured.

- Pawns do not promote on the back rank.

- You can refresh the page to reset the level.

There are 12 puzzles in all. Give them a try!

Read on to learn how the game was made.

Creating Monster Chess

I love chess tactics puzzles, but I hate playing chess. It’s a very contradictory hobby.

Unfortunately, to solve a chess puzzle one must have a deep understanding of the game of chess. Not just the movement of the pieces, mind you, but various tactics that make up fundamental strategy. Mating puzzles are the most obvious, but deeper into the realms of chess puzzles are forks, pins, skewers, sacrifices, discovered checks, zugzwang, and so on. Enjoying a chess puzzle is entirely hinged on knowing why a particular sequence of moves is the single correct answer. Not an easy feat!

Despite this, chess puzzles are beautifully expressive. A board position just begs to be solved, each piece artfully contributing constraints to the possibility space. White to move, mate in 2.

So, I got to thinking. What would a chess puzzle look like if it didn’t assume any prior knowledge of chess, except for the movement of the pieces?

The first thing I removed was the opponent. If we’re no longer playing the game of chess, but simply using the pieces of chess to define a puzzle language, the need for opponent interactions are gone. No more deducing opponent reactions in response to a move.

I recall Puzzmo’s paper puzzle remix of Really Bad Chess. It tweaked the classic mating puzzle format by introducing multiple kings into a single board position and asking for unique checkmate combinations by different pieces. It was a unique spin on the format, but retained too much chess tactic DNA for the result I wanted.

Without an opponent, tactic puzzles fall apart. Mating puzzles are fun, but lacking originality. This is when I stumbled into the central puzzle idea for Monster Chess: the piece that captures morphs into the one taken captive.

With the main idea out of the way, it didn’t take long to pin down the rest of the puzzle constraints. The win condition becomes very natural: clear the board of enemy pieces. Building interesting puzzles means constraining that movement set with pieces that are limited, like pawns. Each puzzle is focused on ensuring the player executes the proper sequence of moves else they get stuck in an irredeemable position.

Lichess-inspired tech stack

Around the time I was thinking about Monster Chess I was investigating the Lichess frontend architecture. Lichess doesn’t use a popular frontend framework, like React or Vue. Instead, it uses a tiny virtual DOM (VDOM) library called snabbdom. The architecture that stitches the snabbdom views, game logic, and server-rendered data together is custom-made by Lichess.

I can speculate why Lichess chose snabbdom over alternatives:

- Lichess predates modern frameworks

- Performance is key, fewer framework layers are a positive

- Maintainability takes precedence over shiny tools

- Lichess has unique UI considerations

Then again, why bother with a VDOM library at all?

I think the answer boils down to philosophical alignment with the Scala backend. Vanilla JS (or jQuery, which would’ve been more relevant in the 2010s) is fundamentally imperative. It’s up to the developer to figure out how they want to stitch together state and UI, and that process often involves wrapping state updates with targeted DOM mutations.

Here’s a simple example comparing a vanilla JS counter to a snabbdom counter.

Vanilla JS:

<button id="counter">Count: 0</button>

<!-- UI updates live a ways away from the DOM -->

<script>

let count = 0

const button = document.getElementById('counter')

button.addEventListener('click', () => {

count++

// Targeted DOM mutation in response to a state update

button.textContent = `Count: ${count}`

})

</script>Snabbdom:

let count = 0

let container = document.getElementById('app')

// UI = f(state)

function view(count) {

return h(

'button',

{

on: {

click: () => {

count++

render()

},

},

},

`Count: ${count}`,

)

}

// The library handles figuring out which bits of state

// correspond to which DOM updates

function render() {

container = patch(container, view(count))

}Snabbdom allows the UI to be represented declaratively as a function of state. Re-rendering concerns the entire application, not just a single unit of the DOM. Developers don’t need to worry about applying DOM updates as a result of state changes; instead they write their UI, write their application logic, and let re-renders handle the rest.

As you might expect, re-rendering the entire DOM tree would be prohibitively expensive and wasteful. Hence the virtual DOM. Snabbdom figures out which DOM nodes need to be updated based on state changes, using the VDOM diff as a guide. Then it updates only the necessary nodes.

Flux architecture for snabbdom

Zooming out a bit, it’s important to note that snabbdom is just a VDOM library. It does not prescribe a technique for managing state in your application or a philosophy around triggering re-renders. That’s the realm of a framework.

Lichess organizes state into controllers. A simplified example looks something like this:

class EditorCtrl {

castlingRights: CastlingRights

onChange() {

// Update state

this.castlingRights = computeCastlingRights();

// And trigger a re-render

this.rerender();

}

}

// UI = f(ctrl)

function view(ctrl: EditorCtrl) {

return h('div.board-editor',

{

on: {

click: () => {

ctrl.onChange()

}

}

},

[...])

}

// Initialize snabbdom onto the current page

export function initModule() {

// Container for game state and logic

const ctrl = new EditorCtrl(rerender);

// First render pass to generate initial DOM

const el = document.getElementById('board-editor')!;

let vnode = patch(el, view(ctrl));

// Trigger re-renders to update the UI after a state change

function rerender() {

vnode = patch(vnode, view(ctrl));

}

}For the purposes of Monster Chess, I didn’t want to worry about manually triggering re-renders on state changes. Any meaningful action in Monster Chess is going to result in a UI update, so I can simply re-render indiscriminately. So, I took a few liberties with the Lichess style of things by adapting the data flow to something that resembles Flux (so 2014, dude).

Here’s a simplified counter example, demonstrating the structure:

class Store {

state = { count: 0 };

// If you don't like mutation, you could always go redux-style:

// this.state = reduce(action)

update(action) {

switch (action.type) {

case "inc":

this.state.count++;

break;

case "dec":

this.state.count--;

break;

}

}

}

const view = (dispatch) => (state) => {

return h("div", [

h("p", `count: ${state.count}`),

h("button", {

on: { click: () => dispatch({ type: "inc" }) }

}, "+"),

h("button", {

on: { click: () => dispatch({ type: "dec" }) }

}, "-"),

]);

};

// Bootstrap boilerplate

window.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", () => {

const container = document.querySelector("#app");

const store = new Store();

// When actions are dispatched to the store, we always

// re-render afterwards.

function dispatch(action: Action) {

store.update(action);

render();

}

const makeView = view(dispatch);

let vnode = patch(container, makeView(store.state));

function render() {

vnode = patch(vnode, makeView(store.state));

}

});The view is constructed with two parameters, dispatch and state. dispatch

passes messages through the store and triggers a re-render. During the render

pass, snabbdom diffs the VDOM and applies changes to the UI based on the most

recent value of state.

I’m sure that Lichess benefits from more control over the render lifecycle of its application, but I definitely appreciate the simplicity of Flux. The view doesn’t call directly into a stateful controller, it merely reads state for a render pass and dispatches the occasional action back into the store.

To put things into more concrete terms, here’s a view into Monster Chess’s

Action type, demonstrating all of the events that are dispatched by the view:

export type Action =

| { type: 'change_mode'; payload: { mode: 'select' } }

| { type: 'select_level'; payload: { level: number } }

| { type: 'select_piece'; payload: { piece: Piece } }

| { type: 'deselect' }

| {

type: 'move'

payload: {

to: Square

original: Piece

captured: Piece | undefined

}

}Why not just use React?

Simply put: novelty. I wanted to see how far I could take a VDOM library without all of the extra framework primitives.

That said, I would generally avoid React for projects like Monster Chess. React

is the kind of tool that is acceptable across the board, but doesn’t excel in

any particular category. Its main draw is mindshare, reducing the number of

decisions made by large teams. Its API is complicated (useEffect dependencies,

anyone?) and its VDOM algorithm is now a complicated concurrent scheduler. For

tiny web games it’s overkill.

If you’re interested in making your own games with this snabbdom stack, check out my game template.