Reminiscing on Flow

in javascript(The type-checker, not the state of deep work)

React’s recent sunsetting of Create React App has me feeling nostalgic.

My first experience with a production web application was a React ecommerce site built with Create React App. I came into the team with zero React experience, hot off of some Angular 2 work and eager to dive into a less-opinionated framework. The year was 2018 and the team (on the frontend, just two of us) was handed the keys to a brand new project that we could scaffold using whatever tools we thought best fit the job.

We knew we wanted to build something with React, but debated two alternative starting templates:

-

Create React App (then, newly released) with Flow

-

One of the many community-maintained templates with TypeScript

You might be surprised that Create React App didn’t originally come bundled with TypeScript1, but the ecosystem was at a very different place back in 2018. Instead, the default type-checker for React applications was Flow, Facebook’s own type-checking framework.

After a couple prototypes, we chose Flow. It felt like a safer bet, since it was built by the same company as the JavaScript framework that powered our app. Flow also handled some React-isms more gracefully than TypeScript, particularly higher-order components where integrations with third-party libraries (e.g. React Router, Redux) led to very complicated scenarios with generics.

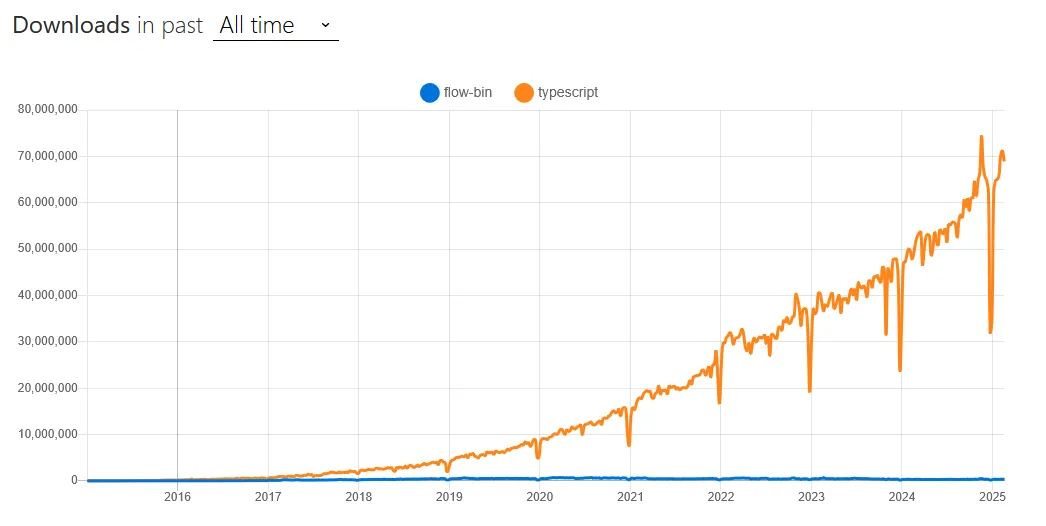

Of all of our stack choices at the start of this project in 2018, choosing Flow is the one that aged the worst. Today, TypeScript is so ubiquitous that removing it from your open source project incites a community outrage2. Why is TypeScript widely accepted as the de facto way to write JavaScript apps, whereas Flow never took off?

I chalk it up to a few different reasons:

-

TypeScript being a superset of JavaScript allowed early adopters to take advantage of JavaScript class features (and advanced proposals, like decorators). In a pre-hooks era, both Angular and React required class syntax for components and the community seemed to widely support using TypeScript as a language superset as opposed to just a type-checker.

-

Full adoption by Angular 2 led to lots of community-driven support for TypeScript types accompanying major libraries via DefinitelyTyped. Meanwhile nobody really used Flow outside of React.

-

Flow alienated users by shipping broad, wide-sweeping breaking changes on a regular cadence. Maintaining a Flow application felt like being subject to Facebook’s whims. Whatever large refactor project was going on at Facebook at the time felt like it directly impacted your app.

-

VSCode has become the standard text editor for new developers and it ships with built-in support for TypeScript.

TypeScript as a language superset

Philosophically, in 2018 the goals of Flow and TypeScript were quite different. TypeScript wasn’t afraid to impose a runtime cost on your application to achieve certain features, like enums and decorators. These features required that your build pipeline either used the TypeScript compiler (which was, and is, incredibly slow) or clobbered together a heaping handful of Babel plugins.

On the other hand, Flow promised to be just JavaScript with types, never making its way into your actual production JavaScript bundle. Since Flow wasn’t a superset of JavaScript, it was simple to set up with existing build pipelines. Just strip the types from the code and you’re good to go.

Back when JavaScript frameworks were class-based (riding on the hype from ES2015), I think developers were more receptive towards bundling in additional language features as part of the normal build pipeline. It was not uncommon to have a handful of polyfills and experimental language features in every large JavaScript project. TypeScript embraced this methodology, simplifying the bundling process by offering support in the TypeScript compiler proper.

Nowadays the stance between the two tools has reversed. The adoption of alternative bundlers that cannot use the TypeScript compiler (esbuild, SWC, and so on) has meant that JavaScript developers are much less likely to make use of TypeScript-specific features. People generally seem less receptive towards TypeScript-specific features (e.g. enums) if they’re easily replaced by a zero-cost alternative (union types). Meanwhile, recent Flow releases added support for enums and React-specific component syntax3. What a reversal!

Community library support

As TypeScript gathered mindshare among JavaScript developers, DefinitelyTyped crushed FlowTyped in terms of open source contribution. By the tail end of 2021, our small team had to maintain quite a few of our own forks of FlowTyped files for many common React libraries (including React Router and Redux)4. Flow definitely felt like an afterthought for open source library developers.

As TypeScript standardized with npm under the @types namespace, FlowTyped

still required a separate CLI. It’s not easy to compete when the alternative

makes installing types as easy as npm install @types/my-package.

Breaking things

I remember distinctly that upgrading Flow to new releases was such a drag. Not only that, but it was a regular occurrence. New Flow releases brought wide-sweeping changes, often with new syntax and many deprecations. This problem was so well-known in the community that Flow actually released a blog post on the subject in 2019: Upgrading Flow Codebases.

For the most part, I don’t mind if improvements to Flow means new violations in my existing codebase pointing to legitimate issues. What I do mind is that many of these problematic Flow releases felt more like Flow rearchitecting itself around fundamental issues that propagated down to users as new syntax requirements. It did not often feel like the cost to upgrade matched the benefit to my codebase.

A couple examples that I still remember nearly 6 years later:

LSP, tooling, and the rise of VSCode

In the early days, the Flow language server was on par with TypeScript’s. Both tools were newly emerging and often ran into issues that required restarting the language server to re-index your codebase.

VSCode was not as ubiquitous in those days as it is today, though it was definitely an emerging star. Facebook was actually working on its own IDE at the time, built on top of Atom. Nuclide promised deep integration with Flow and React, and gathered a ton of excitement from our team. Too bad it was retired in December of 2018.

As time went on and adoption of VSCode skyrocketed, Flow support lagged behind. The TypeScript language server made huge improvements in consistency and stability and was pre-installed in every VSCode installation. Meanwhile Flow crashed with any dependency change, and installing the Flow extension involves digging into your built-in VSCode settings and disabling JavaScript/TypeScript language support.

Towards TypeScript

As our Flow application grew from 3-month unicorn to 3-year grizzled veteran, Flow really started to wear developers on our team down. It was a constant onboarding pain as developers struggled to set up VSCode and cope with some of the Flow language server idiosyncrasies. Refactoring to TypeScript was an inevitable conversation repeated with every new hire.

The point of this blog post is not to bag on Flow. I still have a ton of respect for the project and its original goal of simplicity: “JavaScript with types”. Although that goals lives on via JSDoc, Flow is an important milestone to remember as type annotations are formally discussed by TC39.

Before leaving the company, I remember tasking out a large project detailing the entire process of converting our Flow codebase to TypeScript. I wonder if it was ever finished.

Footnotes

-

TypeScript support was added in 2019 with the v2 release. ↩

-

For another example, see Svelte’s move from TypeScript to JSDoc. ↩

-

The move away from “JavaScript with types” is documented in this blog post: Clarity on Flow’s Direction and Open Source Engagement. ↩

-

If you’ve never looked at one of the type files for some of your favorite libraries, they can be rather cryptic. ↩