Paper Puzzle Remixes

in puzzles, gamesThe holidays are always a great time for puzzles. My parents still receive print newspapers, offering an ideal opportunity to catch up on crosswords. This year I also picked up NYT’s Puzzle Mania, a treasure-trove of paper puzzle goodness. Just a few days ago my partner and I finished the whopping 50x50 crossword puzzle. That’s over 1000 clues!

What struck me as especially interesting with Puzzle Mania were the paper remixes of the popular “-dles”:1 Wordle, Spelling Bee, and Connections. Each remix tweaks the digital puzzle form so that it suits a printed medium, changing a few mechanics but keeping the puzzle evocative of its original design. Puzzmo did something similar with their Crossword Vol. 1, offering print versions of Really Bad Chess and Flipart.

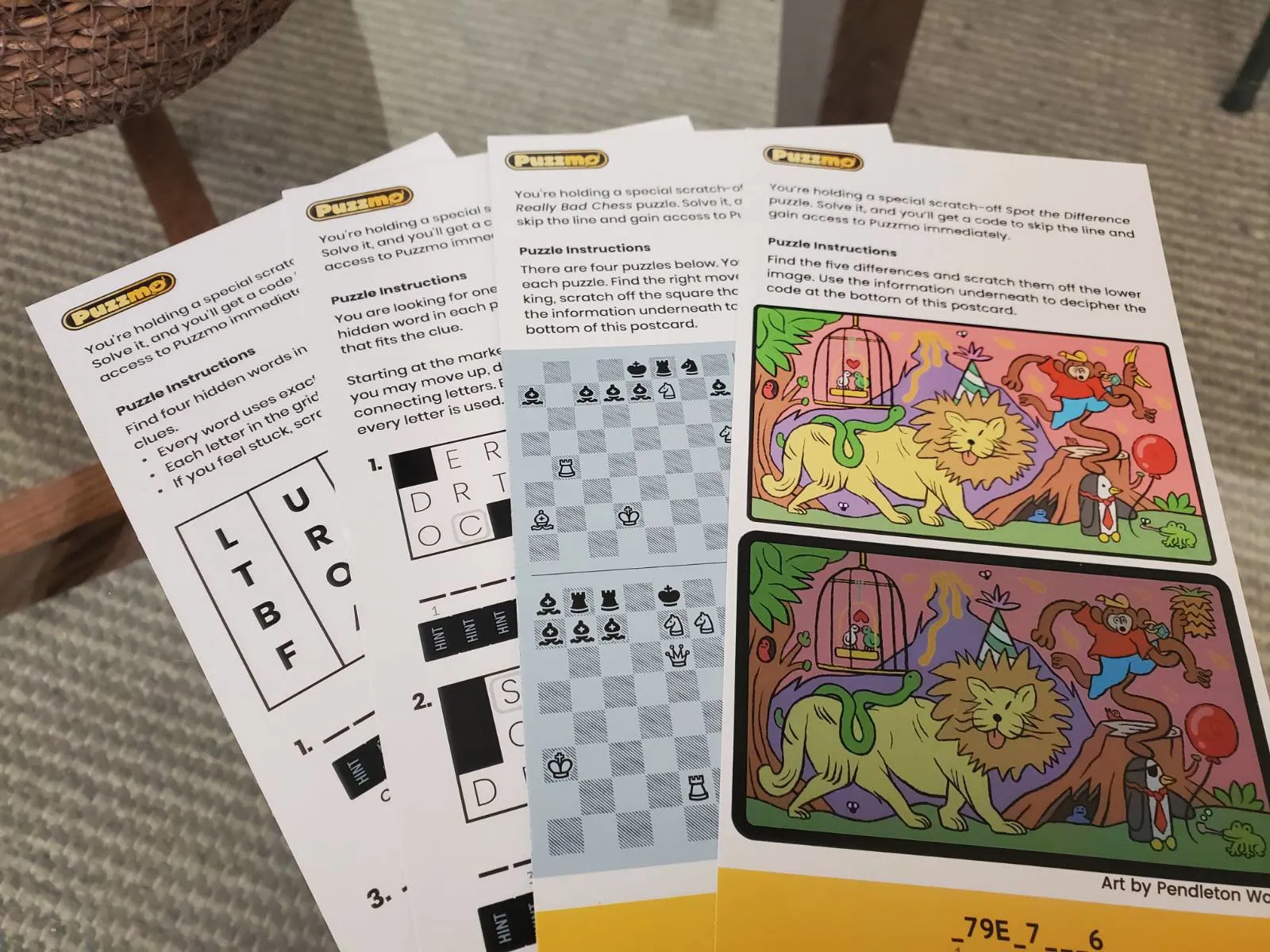

In fact, when Puzzmo soft-launched they sent out beta invites via physical postcards to your address. Solve the puzzle on the postcard to unlock your way into the app.

The first and third pictured are remixes of Zach Gage games: Typeshift and Really Bad Chess. Typeshift is the more interesting of the two, since the digital version relies on a clever sliding interface to differentiate the game from a simple wordsearch. Adapting the game to print means the player can no longer find words by randomly moving the slider up and down.2 It also means lowering the number of possible words to simplify the search.

I think the popularity of “-dle” puzzle games, the kind of daily games that one finds on NYT and Puzzmo, have to do with their resemblance to newspaper puzzles. They’re short and snackable, perfect while waiting for coffee to brew. They’re also crunchy enough that the player makes observable improvements over a long period of time, often in the form of a solving streak.

However, despite that resemblance there’s a design tension that arises when adapting a digital puzzle into a print puzzle. What kinds of mechanics are translatable and why? How do the designers behind games like Flipart approach print adaptation of their digital games?

Zach Gage (creator of Flipart) gives some insight into the process in the Crossword Vol. 1 collection:

When we first started thinking about what kinds of puzzles we could make in print, we felt like Flipart was one Puzzmo game that truly could not work on paper. It was friend and fellow game designer JW Nijman who suggested a grid with embedded shapes that players would have to draw corresponding shapes on top of. […] I didn’t want players to have to do shape rotation in their heads (this is tough for many people!), so I brought JW’s idea to Jack…

I recommend playing through a game of Flipart to get a sense of the difficulties Zach alludes to in this quote. A game of Flipart only takes tens of seconds. It’s borderline instinctual; the ocular faculties take control as shapes rotate to avoid overlapping.

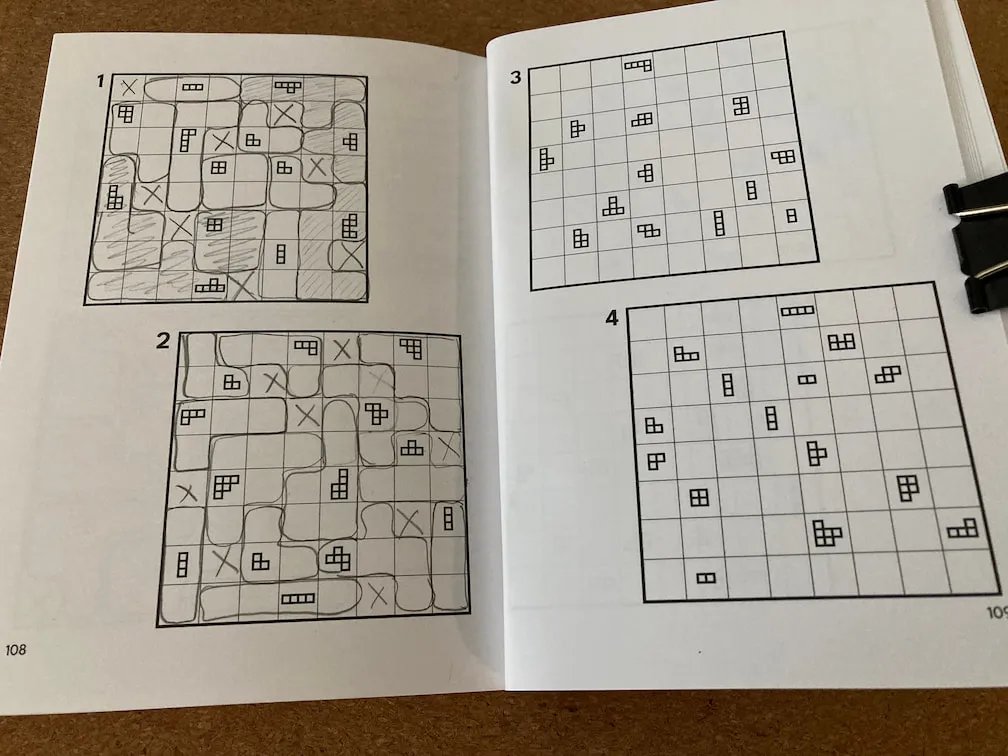

In contrast, the print version of the game is slow and methodical. Rotation is removed in favor of drawing the shape as-is. The fundamental constraint is drawing the shape in the grid such that the drawn shape contains the square that originally depicted it. Shapes cannot rotate and drawings cannot overlap. Print Flipart is much more of a logic puzzle.3

Both the digital and print forms of Flipart play to the strengths of their medium. The digital form takes advantage of the fact that the computer can trivially render shapes in different rotations, something that’s incredibly difficult for the human mind (and tedious to draw). The print form remains evocative of the digital, but ditches rotation in favor of something easier to both conceptualize and draw.

Converting a digital puzzle to a print puzzle is an interesting exercise. What can we learn from the process? A few rules come to mind:

-

Keep state simple. Unlike their digital counterparts, print puzzles cannot represent game state that often changes or changes in unintuitive ways (like rotations in Flipart). The best print puzzles have the player fill in the game state as they progress, e.g. letters in crosswords, numbers in sudoku, and shapes in print Flipart.

-

Complicated rule evaluations are a better fit for digital puzzles. Chess puzzles often feel more like an academic exercise than a casual puzzle, as the player must not only think about their own optimal move, but also the optimal response from their opponent. A puzzle that requires multiple back-and-forth turns quickly balloons into an overwhelming number of possibilities.

-

Rethink UI affordances. On the web, Typeshift uses a vertical slider to add extra flavor to the puzzle-solving experience. On paper, implementing a vertical slider is impossible. To compensate, the overall complexity of the puzzle is reduced.

-

Grids make for great playgrounds. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that crosswords and sudokus are confined to a grid. The grid is satisfying to fill and clearly denotes progress. It also provides a natural place to store game state.

I also want to shout-out a fantastic game that released last year: LOK Digital. It’s relevant to this whole conversation because it actually goes in the reverse direction, adapting a print puzzle into a digital form. Because the rules of LOK are heavily reliant on rules evaluation, I personally think the digital adaptation is the way to go. It makes the overall experience quite a bit more enjoyable.

Footnotes

-

Not my favorite term, but an apt description of the genre after the popularity of Wordle. ↩

-

Not like I’ve done that before, obviously. ↩

-

The print Flipart puzzles are surprisingly similar to the tetris puzzles from The Witness. ↩