Exploring the Writebook Source Code

in rubyEarlier this year 37signals released Writebook, a self-hosted book publishing platform. It’s offering number two from their ONCE series, pitched as the antithesis of SaaS. Buy it once and own it for life, but run it on your own infrastructure.

Unlike the other ONCE offering, Writebook is totally free. When you “purchase” it through the ONCE checkout, they hook you up with the source code and a convenient means of downloading the software on a remote service. Since the software is free (but not open source) I thought it’s fair game to read through it and write a little post about its implementation. It’s not everyday that we can study a production Rails application made by the same folks behind Rails itself.

Note: I’ll often omit code for the sake of brevity with a “—snip” marker. I encourage you to download Writebook yourself and follow along so you can discover the complete context.

Run the thing

A good place to start is the application entrypoint: Procfile. I think

Procfile is a holdover from the Heroku-era, when everyone was hosting their

Rails applications on free-tier dynos (RIP). Either way, it describes the

top-level processes that make up the server:

web: bundle exec thrust bin/start-app

redis: redis-server config/redis.conf

workers: FORK_PER_JOB=false INTERVAL=0.1 bundle exec resque-poolNice and simple. There are three main components:

web, Writebook’s web and application serverredis, the backing database for the application cache and asynchronous workersworkers, the actual process that executes asynchronous tasks

The only other infrastructure of note is the application database, which is running as a single file via SQLite3.

bundle exec thrust bin/start-app might be surprising for folks expecting

bin/rails server as the main Rails process. thrust is the command invocation

for thruster, a fairly recent

HTTP proxy developed by 37signals specifically for ONCE projects. It provides a

similar role to nginx, a web server that sits in front of the main Rails process

to handle static file caching and TLS. The thrust command takes a single

argument, bin/start-app, which contains your standard bin/rails s

invocation, booting up the application server.

Redis and workers fill out the rest of the stack. Redis fills a few different

purposes for Writebook, serving as the application cache and the task queue for

asynchronous work. I’m a little surprised

Solid Queue and

Solid Cache don’t make an appearance,

swapping out Redis for the primary data store (SQLite in this case). But then

again, perhaps it’s more cost-efficient to run Redis in this case, since

Writebook probably wants to be self-hosted on minimal hardware (and not have

particular SSD requirements).

You can run the application locally with foreman (note you’ll need Redis installed, as well as libvips for image processing):

foreman startPages that render markdown

When it comes to the textual content of books created with Writebook, everything

boils down to the Page model and it’s fancy has_markdown :body invocation:

class Page < ApplicationRecord

# --snip

has_markdown :body

endThat single line of code sets up an

ActionText

association with Page under the attribute name body. All textual content in

Writebook is stored in the respective ActionText table, saved as raw markdown.

Take a look at this Rails console query for an example:

writebook(dev)> Page.first.body.content

=> "# Welcome to Writebook\n\nThanks for downloading Writebook...To my surprise, has_markdown is not actually a Rails ActionText built-in. It’s

manually extended into Rails by Writebook in

lib/rails_ext/action_text_has_markdown.rb, along with a couple other files

that integrate ActionText with the third-party gem

redcarpet:

module ActionText

module HasMarkdown

extend ActiveSupport::Concern

class_methods do

def has_markdown(name, strict_loading: strict_loading_by_default)

# --snip

has_one :"markdown_#{name}", -> { where(name: name) },

class_name: "ActionText::Markdown", as: :record, inverse_of: :record, autosave: true, dependent: :destroy,

strict_loading: strict_loading

# --snip

end

end

end

end

# ...

module ActionText

class Markdown < Record

# --snip

mattr_accessor :renderer, default: Redcarpet::Markdown.new(

Redcarpet::Render::HTML.new(DEFAULT_RENDERER_OPTIONS), DEFAULT_MARKDOWN_EXTENSIONS)

belongs_to :record, polymorphic: true, touch: true

def to_html

(renderer.try(:call) || renderer).render(content).html_safe

end

end

endlib/rails_ext/ as the folder name is very intentional. The code belongs in

lib/ and not app/lib/ because it’s completely agnostic to the application.

It’s good ol’ reusable Ruby code for any Rails application that has ActionText.

rails_ext/ stands for “Rails extension”, a common naming convention for vendor

monkey patches that might live in a Rails application. This code re-opens an

existing namespace (the ActionText module, in this case) and adds new

functionality (ActionText::Markdown). Within the application, users can use

ActionText::Markdown without evet knowing it’s not a Rails built-in.

This is a neat little implementation for adding markdown support to ActionText, which is normally just a rich text format coupled to the Trix editor.

Beyond pages

Page is certainly the most important data model when it comes to the core

functionality of Writebook: writing and rendering markdown. The platform

supports a couple other fundamental data types, that being Section and

Picture, that can be assembled alongside Pages to make up an entire Book.

The model hierarchy of a Book looks something like this:

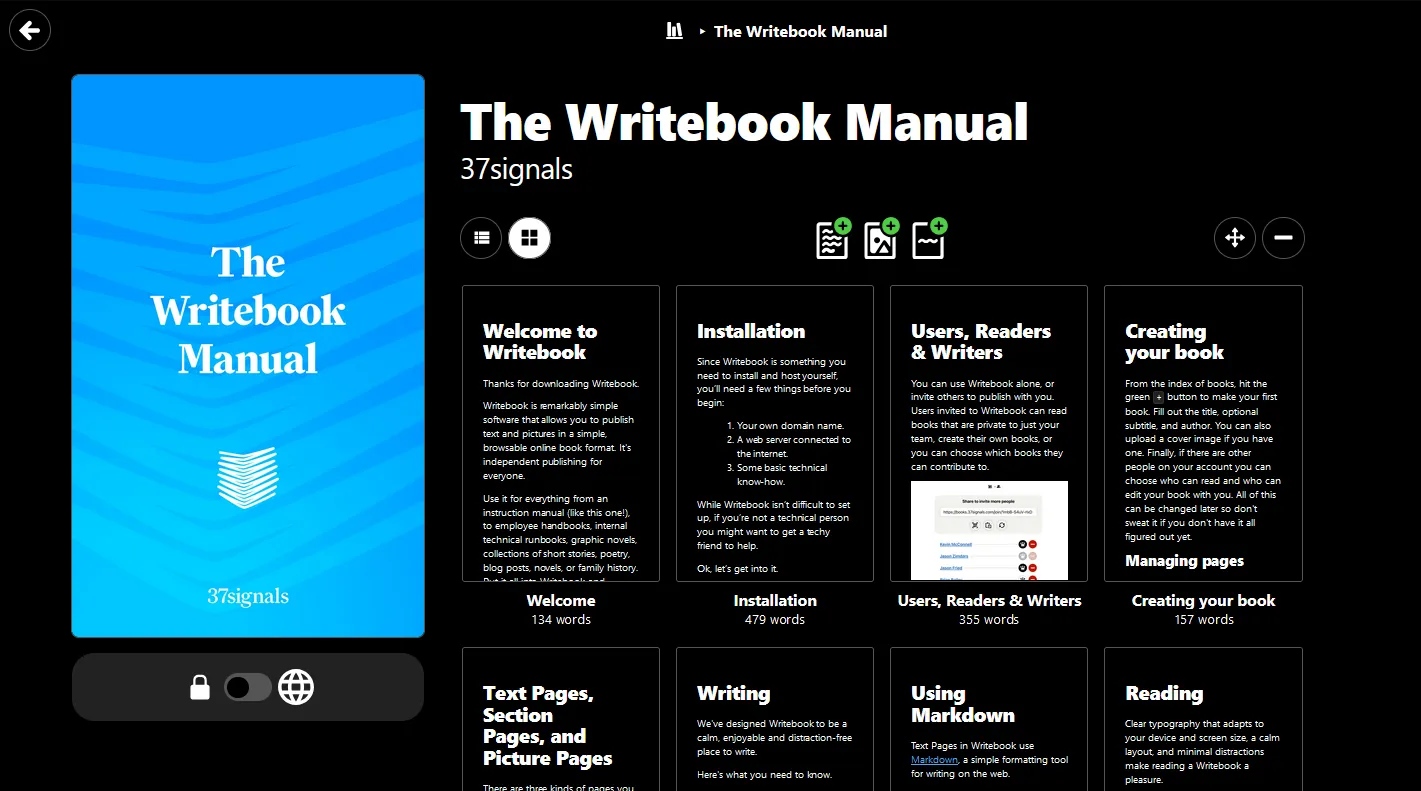

Book = Leaf[], where Leaf = Page | Section | PictureIn other words, a Book is made up of many Leaf instances (leaves), where a

Leaf is either a Page (markdown content), a Section (basically a page

break with a title), or a Picture (a full-height image).

You can see the three different Leaf kinds near the center of the image,

representing the three different types of content that can be added to a Book.

This relationship is clearly represented by the Rails associations in the

respective models:

# app/models/book.rb

class Book < ApplicationRecord

# --snip

has_many :leaves, dependent: :destroy

end

# app/models/leaf.rb

class Leaf < ApplicationRecord

# --snip

belongs_to :book, touch: true

delegated_type :leafable, types: Leafable::TYPES, dependent: :destroy

positioned_within :book, association: :leaves, filter: :active

endWell, maybe not completely “clearly”. One thing that’s interesting about this

implementation is the use of a Rails concern and delegated_type to represent

the three kinds of leaves:

module Leafable

extend ActiveSupport::Concern

TYPES = %w[ Page Section Picture ]

included do

has_one :leaf, as: :leafable, inverse_of: :leafable, touch: true

has_one :book, through: :leaf

delegate :title, to: :leaf

end

endThere are three kinds of Leaf that Writebook supports: Page, Section, and

Picture. Each Leaf contains different attributes according to its kind. A

Page has ActionText::Markdown content, a Section has plaintext, and a

Picture has an image upload and a caption. However, despite their difference

in schema, each of the three Leaf kinds is used in the exact same way by

Book. In other words, Book doesn’t care which kind of Leaf it holds a

reference to.

This is where delegated_type comes into play. With delegated_type, all of

the shared attributes among our three Leaf kinds live on the “superclass”

record, Leaf. Alongside those shared attributes is a leafable_type, denoting

which “subclass” the Leaf falls into, one of "Page", "Section", or

"Picture". When we call Leaf#leafable, we fetch data from the matching

“subclass” table to pull the non-shared attributes for that Leaf.

The pattern is made clear when querying in the Rails console:

writebook(dev)> Leaf.first.leafable

SELECT "leaves".* FROM "leaves" ORDER BY "leaves"."id" ASC LIMIT 1

SELECT "pages".* FROM "pages" WHERE "pages"."id" = ?Rails knows from leafable_type that Leaf.first is a Page. To read the rest

of that Leaf’s attributes, we need to fetch the Page from the pages table

associated to the leafable_id on the record. Same deal for Section and

Picture.

Another thing that’s interesting about Writebook’s use of delegated_type is

that the Leaf model isn’t exposed on a route:

resources :books, except: %i[ index show ] do

# --snip

resources :sections

resources :pictures

resources :pages

endThis makes a ton of sense because the concept of Leaf isn’t exactly

“user-facing”. It’s more of an implementation detail. The relation between the

three different Leafable types is exposed by some smart inheritance in each of

the “subclasses”. Take SectionsController as an example:

class SectionsController < LeafablesController

private

def new_leafable

Section.new leafable_params

end

def leafable_params

params.fetch(:section, {}).permit(:body, :theme)

.with_defaults(body: default_body)

end

def default_body

params.fetch(:leaf, {})[:title]

end

endAll of the public controller handlers are implemented in LeafablesController,

presumably because each Leafable is roughly handled in the same way. The only

difference is the params object sent along in the request to create a new

Leaf.

class LeafablesController < ApplicationController

# --snip

def create

@leaf = @book.press new_leafable, leaf_params

position_new_leaf @leaf

end

endI appreciate the nomenclature of Book#press to create add a new Leaf to a

Book instance. Very clever.

Authentication and users

My go-to when setting up authentication with Rails is

devise since it’s an easy drop-in

component. Writebook instead implements its own lightweight authentication

around the built-in has_secure_password:

class User < ApplicationRecord

include Role, Transferable

has_many :sessions, dependent: :destroy

has_secure_password validations: false

has_many :accesses, dependent: :destroy

has_many :books, through: :accesses

# --snip

endThe authentication domain in Writebook is surprisingly complicated because the

application supports multiple users with different roles and access permissions,

but most of it is revealed through the User model.

The first time you visit a Writebook instance, you’re asked to provide an email

and password to create the first Account and User. This is represented via a

non-ActiveRecord model class, FirstRun:

class FirstRun

ACCOUNT_NAME = "Writebook"

def self.create!(user_params)

account = Account.create!(name: ACCOUNT_NAME)

User.create!(user_params.merge(role: :administrator)).tap do |user|

DemoContent.create_manual(user)

end

end

endWhether or not a user can access or edit a book is determined by the

Book::Accessable concern. Basically, a Book has many Access objects

associated with it, each representing a user and a permission. Here’s the

Access created for the DemoContent referenced in FirstRun:

#<Access:0x00007f06efac0538

id: 1,

user_id: 1,

book_id: 1,

level: "editor"

#--snip>Likewise, when new users are invited to a book, they are assigned an Access

level that matches their permissions (reader or editor). Note that all of this

access-stuff is for books that have not yet been published to the web for public

viewing. Writebook allows you to invite early readers or editors for feedback

before you go live.

Whoa, whoa, whoa. What is this rate_limit on the SessionsController?

class SessionsController < ApplicationController

allow_unauthenticated_access only: %i[ new create ]

rate_limit to: 10,

within: 3.minutes,

only: :create,

with: -> { render_rejection :too_many_requests }Rails 8 comes with built-in rate limiting support? That’s awesome.

Style notes

I like the occasional nesting of concerns under model classes, e.g.

Book::Sluggable. These concerns aren’t reusable (hence the nesting), but they

nicely encapsulate a particular piece of functionality with a callback and a

method.

# app/models/book/sluggable.rb

module Book::Sluggable

extend ActiveSupport::Concern

included do

before_save :generate_slug, if: -> { slug.blank? }

end

def generate_slug

self.slug = title.parameterize

end

endOver on the HTML-side, Writebook doesn’t depend on a CSS framework. All of the classes are hand-written and applied in a very flexible, atomic manner:

<div class="page-toolbar fill-selected align-center gap-half ..."></div>These classes are grouped together in a single file, utilities.css. Who needs

Tailwind?

.justify-end {

justify-content: end;

}

.justify-start {

justify-content: start;

}

.justify-center {

justify-content: center;

}

.justify-space-between {

justify-content: space-between;

}

/* --snip */I’m also surprised at how little JavaScript is necessary for Writebook. There

are only a handful of StimulusJS controllers, each of which encompasses a tiny

amount of code suited to a generic purpose. The AutosaveController is probably

my favorite:

import { Controller } from '@hotwired/stimulus'

import { submitForm } from 'helpers/form_helpers'

const AUTOSAVE_INTERVAL = 3000

export default class extends Controller {

static classes = ['clean', 'dirty', 'saving']

#timer

// Lifecycle

disconnect() {

this.submit()

}

// Actions

async submit() {

if (this.#dirty) {

await this.#save()

}

}

change(event) {

if (event.target.form === this.element && !this.#dirty) {

this.#scheduleSave()

this.#updateAppearance()

}

}

// Private

async #save() {

this.#updateAppearance(true)

this.#resetTimer()

await submitForm(this.element)

this.#updateAppearance()

}

#updateAppearance(saving = false) {

this.element.classList.toggle(this.cleanClass, !this.#dirty)

this.element.classList.toggle(this.dirtyClass, this.#dirty)

this.element.classList.toggle(this.savingClass, saving)

}

#scheduleSave() {

this.#timer = setTimeout(() => this.#save(), AUTOSAVE_INTERVAL)

}

#resetTimer() {

clearTimeout(this.#timer)

this.#timer = null

}

get #dirty() {

return !!this.#timer

}

}When you’re editing markdown content with Writebook, this handy controller automatically saves your work. I especially appreciate the disconnect handler that ensures your work is always persisted, even when you navigate out of the form to another area of the application.

Closing thoughts

There’s more to explore here, particularly on the HTML side of things where Hotwire does a lot of the heavy lifting. Unfortunately I’m not a good steward for that exploration since most of my Rails experience involves some sort of API/React split. The nuances of HTML-over-the-wire are over my head.

That said I’m impressed with Writebook’s data model, it’s easy to grok thanks to

some thoughtful naming and strong application of lesser-known Rails features

(e.g. delegated_type). I hope this code exploration was helpful and inspires

the practice of reading code for fun.